I can still feel the icy wind cutting through my coat. The sting of the rain piercing the exposed skin on my face. I can still feel the pit in my stomach. The feeling of extreme sadness and overwhelm as I looked around and tried to understand what happened where I stood. Because it did, and it is important for us to not only acknowledge that, but to try and understand what happened so that we can stand together and ensure that it never happens again.

I was reluctant to visit a concentration camp. I am an empath and I knew that I would struggle with the feeling and the emotion that putting myself in that situation would expose. But at the same time I felt like it was important to understand and to remember the people and the families who were so directly impacted by the horrors of this part of our history. They don’t get a choice to avoid these realities, so I wanted to try and understand what they went through, and to listen to their stories.

I was reluctant to visit a concentration camp. I am an empath and I knew that I would struggle with the feeling and the emotion that putting myself in that situation would expose. But at the same time I felt like it was important to understand and to remember the people and the families who were so directly impacted by the horrors of this part of our history. They don’t get a choice to avoid these realities, so I wanted to try and understand what they went through, and to listen to their stories.

When my husband and I were planning our visit to Germany I knew a key part of our journey would be exposing ourselves to its history. While there are so many layers that make up the foundations of the country, the history that interested us most was that which was centred around World War II. We were drawn to Berlin in particular as it is a place so full and rich with history that it felt as though part of properly experiencing the city was to fully immerse ourselves in it.

And we did just that. I haven’t written about our time in Berlin on the blog because I wasn’t sure how to. How do you capture the experience of something so powerful, something that cannot be said to be enjoyable, but something that changes how you see the world? I’m still not sure, but I am going to try.

There are many ways to see Berlin, it is a richly diverse city with many layers. It is a city full of life that contrasts the historical and the old parts with the new and modern which push the boundaries of expectation. Diversity is celebrated and something interesting lies around every corner.

With such a short time there, we chose to devote ourselves to the history and learning about the past. It was a solemn look back in time, and the freezing, drizzly winter weather that followed us around seemed to understand this.

We got lost in the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, walking through the endless rows of concrete and feeling humbled by the size. Taking deep breaths as we descended into the middle of the maze unprepared for the feeling of overwhelm that followed.

We got lost in the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, walking through the endless rows of concrete and feeling humbled by the size. Taking deep breaths as we descended into the middle of the maze unprepared for the feeling of overwhelm that followed.

We stood on the footpath looking into the carpark that now sits on the location of Hitler’s bunker where he took his last breath. Nothing but a simple sign to tell you that you’re in the right place. An acknowledgement to the history but nothing more.

We walked through tunnels where only the lucky people could hide when the bombs came.

And we learned even more at the museum that sits upon the site of the Gestapo headquarters, reading countless stories from history, all the while the thoughts of what happened on this soil made my skin crawl.

But among all of this, nothing was more impactful than our visit to Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp.

When planning our visit, I knew I wanted to do a guided tour as the information and insight that a knowledgeable guide could provide would be invaluable. I however was very cautious as to the company that I would choose. I wanted to make sure that any money I handed over would be used to protect and preserve rather than go into the hands of a tour company just looking for profit.

When planning our visit, I knew I wanted to do a guided tour as the information and insight that a knowledgeable guide could provide would be invaluable. I however was very cautious as to the company that I would choose. I wanted to make sure that any money I handed over would be used to protect and preserve rather than go into the hands of a tour company just looking for profit.

It’s not essential to join a tour and there are audio guides available to help you navigate through, however after much research, we chose a guided tour with The Friends of Sachsenhausen Memorial and Museum and I highly recommend to do it this way. The guides are all volunteers and the money from your ticket goes directly help to preserve the Sachsenhausen Memorial and Museum.

Prices were only 14 € per person and we met in Berlin at Potsdamer Platz at the historic traffic light. We stood, waiting for our meeting time on the coldest morning of our journey so far. The weather alternated between sleet and snow and we wrapped our scarves around us tighter trying to brace from the wind and stop the chill getting through.

Our journey began on the train to Oranienburg giving us an interesting look at Berlin from a new angle. The journey took around an hour and when we disembarked our guide was there ready to greet us.

She was originally from the UK but had been living and studying in Germany for a few years. She talked to us about what we should expect from the tour and she answered the burning question I had, how could you volunteer to come here every day? Wouldn’t that have a significant emotional impact?

That was true. She told us that she can only lead one tour per week through Sachsenhausen (the german pronunciation being zaksen hauzen), as it can be quite emotionally draining. She does this though to honor her grandfather and the history of the people and the country.

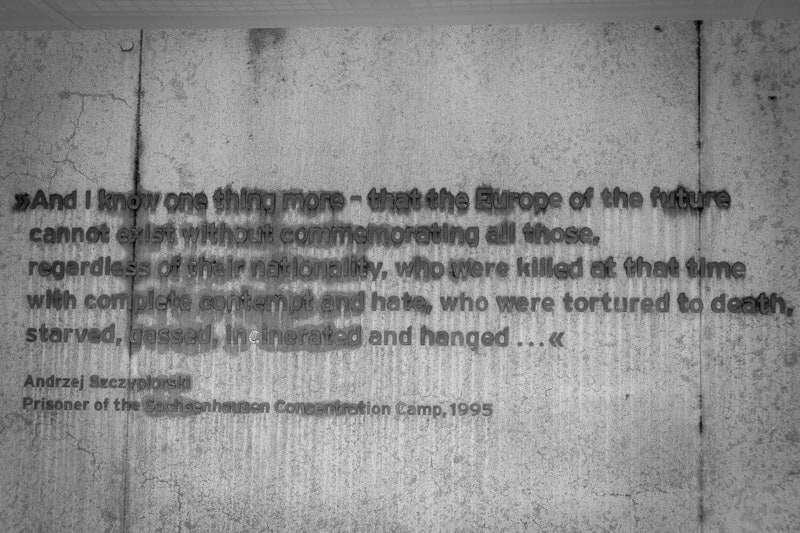

She told us the story of her grandfather, who had fought for England in WWII and had been involved in the liberation of a concentration camp – not this one, but another similar. It was something that was quite painful for him to recall so like many veterans, he just never spoke about it. That was until he was nearing the end of his life. He spoke to our guide and told her that he felt it was important to never forget what people are capable of, and that by remembering we help ensure that this will never happen again. We owe it to the people who lost their lives and their families to not forget.

This story really impacted me, and I felt that was exactly the reason that I had come.

From the train platform, we began our walk. We would walk through the town of Oranienburg and through the gates of the camp following the exact path in which prisoners were marched as they were brought here from Berlin.

From the train platform, we began our walk. We would walk through the town of Oranienburg and through the gates of the camp following the exact path in which prisoners were marched as they were brought here from Berlin.

As we walked through the town we talked about how the townspeople had to have known about the horrors that went on in the camp due to the proximity to the town. As we got closer we looked at the houses which were once owned and lived in by Nazi Soldiers, and we wondered who was living there now and what they thought about the history that surrounded them.

We walked through the gates and past a large building which we learned was once the training ground for Nazi Officers. It is now a training ground for the German Police Force – the building itself a chilling reminder to them every single day of what they are protecting Germany from.

The air around us got colder as we walked in through the gates and down the road towards the camp, the same road that led the remaining 33 000 prisoners on a death march north towards the sea as the camp was evacuated in April 1945, with 6 000 of those prisoners dying before the march was liberated by the Soviet and US armies.

It felt strange to be so close to the horrors of our past. A past that was only a couple of generations ago. I wrapped my giant oversized scarf around my neck and face and braced myself, not only for the cold, but for the stories and the history we were about to walk into.

At the gate to the camp, we saw the same sign that every prisoner would see upon entering which reads “arbeit macht frei” which translates to ‘work makes you free’. A symbol of false hope that if the prisoners worked hard and completed their labour effectively serving their sentence, they would be released.

At the gate to the camp, we saw the same sign that every prisoner would see upon entering which reads “arbeit macht frei” which translates to ‘work makes you free’. A symbol of false hope that if the prisoners worked hard and completed their labour effectively serving their sentence, they would be released.

I think it’s important to acknowledge here that like any tourist destination, you will see people taking selfies. The most common place I witnessed this was in front of this sign. For me, I was horrified at first, this sign being a fabricated symbol of hope to the prisoners to hide the conditions that lay before them. And while this was not a death camp, many did not leave due to malnutrition, disease or general miss-treatment. To give them hope was cruel. And to celebrate this with a smiling selfie I found unfathomable. But I soon realised that this was wasted energy and really the only thing to do is move on and focus on your own experience.

For me, I decided before I went that I did want to take some photographs because I wanted to share this experience here. I chose to do it in a way that felt comfortable to me, and that meant being respectful in the intent of my pictures, and also the subject.

That is my only comment if you find yourself at a place like this – there is nothing wrong with taking photographs if allowed, but always remember to be respectful of your surroundings.

At these gates prisoners were also categorised based on their ‘crime’. They would wear coloured triangle patches on their uniforms to clearly identify them to the guards and other prisoners. These patches also worked as a class system that influenced the types of labour they would have to undertake.

At these gates prisoners were also categorised based on their ‘crime’. They would wear coloured triangle patches on their uniforms to clearly identify them to the guards and other prisoners. These patches also worked as a class system that influenced the types of labour they would have to undertake.

With construction completed on the camp using prison labour in 1938, Sachsenhausen’s population was mostly political prisoners, however as World War II began, there was a shift as more and more people were imprisoned for racial crimes. Following the invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, it also became a place to house thousands of Soviet prisoners of war.

Due to the proximity of the camp to Berlin, it also became a centre for the operations and personnel training of concentration camps.

In 1942, an extermination centre was built, again using prisoner labour. The site of which is where we ended our tour of the grounds. To illustrate its effectiveness, 96 Jews were shot on the first day of its operation. The site we walked through contained the area used for hangings, which were mostly for the Soviet prisoners of war, and the building site where SS Soldiers would stand in small rooms and shoot Jewish prisoners from behind a wall. And then there was the crematorium which was built on site in 1940 after the need became apparent.

This was easily one of the most emotional sites I have ever visited. Speaking about the atrocities that occurred, it becomes hard to actually believe. The sheer scale of death that occurred on that ground is unfathomable.

As I walked through, I couldn’t help but feel the emotion of my surroundings. People all around were quiet yet emotional and I wondered if maybe they could have known someone who lost their life here. As I left and began to walk back to the museum I realised that I had been holding my breath. I could feel the tears running down my cheek, an acknowledgement of the unnecessary loss and the sadness that walks hand in hand with history.

There is something very interesting about an experience like this. It has the ability to alter the way you see the world. And while I cannot say that I enjoyed my time at the camp, I respect it for everything that it gave me. This experience provided a different perspective on the past, a promise for the future and a glimpse at every shade of humanity from the unfathomable to the courageous. It was truly unforgettable.

One thing that I always want to try and do is to be able to capture the emotion and the feelings that consumed me in a moment and share them through words and images. Maybe you won’t ever set foot in a place like this or maybe you have had the opportunity. Whatever the situation, I hope that through this post you are able to take a small piece of what this experience taught me and carry that with you into the future, because like I said before, we have a responsibility to make sure that these stories are never forgotten.

One thing that I always want to try and do is to be able to capture the emotion and the feelings that consumed me in a moment and share them through words and images. Maybe you won’t ever set foot in a place like this or maybe you have had the opportunity. Whatever the situation, I hope that through this post you are able to take a small piece of what this experience taught me and carry that with you into the future, because like I said before, we have a responsibility to make sure that these stories are never forgotten.

Also I know there are not many photographs in this post – I tried my best to only take the images that I thought told the story and nothing more. That was a really important part of the experience for me. When I was editing them I just couldn’t get the colours right which is why they are all in black and white. Once I made that change they became perfect to illustrate this story.

Travel gives us the ability to see things in a new way and to open up our experiences to things we could never even imagine. For that, I am truly grateful.

Stats and background information from https://www.holocaust.cz/en/history/concentration-camps-and-ghettos/sachsenhausen-3/

Hugo

Awesome article.

Wendy

Dear Sally, it had to take enormous courage for you to even choose to go to this sacred ground that carries still the voices and emotions of each person who was there, in whatever capacity they were there. I also am empathetic, would avoid a place like that at all costs, as well as Ground Zero in NY City, knowing myself well enough. As a child of 9, my school class was shown films of the Holocaust and the bombing of Hiroshima. The fear it brought up in me shaped my life from then on. I did go to an old abandoned women’s prison in the state I live in, one that held people in solitary confinement, that was, unfathomably, being re-done into a “retreat” site. It so far hasn’t been able to do that. I was totally unsettled being there, trying hard to keep my center, but I would never go back nor subject myself to such an experience willingly again. For you to have done that and come through it and brought your experience to us is priceless, and I thank you for your compassion and insight and bravery.

Sally

Hi Wendy. I think it is important sometimes for us to get a bit uncomfortable in order to better understand our history and in some way to honour those who went through such horrors. I don’t know how I feel about a prison being turned into a retreat, I don’t think that would be somewhere I could enjoy either. Thank you for your comment and sharing in the conversation about what it’s really like to visit a place like this.